Drawing in the Natural Sciences

Introduction: Jerwood Artist in Residence 2010

After observing the judging process of the Jerwood Drawing Prize 2010 and viewing thousands of fine art drawings, I realized that with each new batch of submissions, I was hoping to see drawings that are increasingly rare in the art world: representations of natural phenomena, maps, and plans. This sparked my curiosity about contemporary drawing practices beyond the art world, specifically within the Natural Sciences.

Some of my favourite drawings are 19th-century geological, astronomical, and zoological illustrations created to explore and understand their subjects. This led me to investigate whether drawing still plays a role in knowledge formation in the Natural Sciences at institutions like University College London, Kew Gardens, and The Natural History Museum.

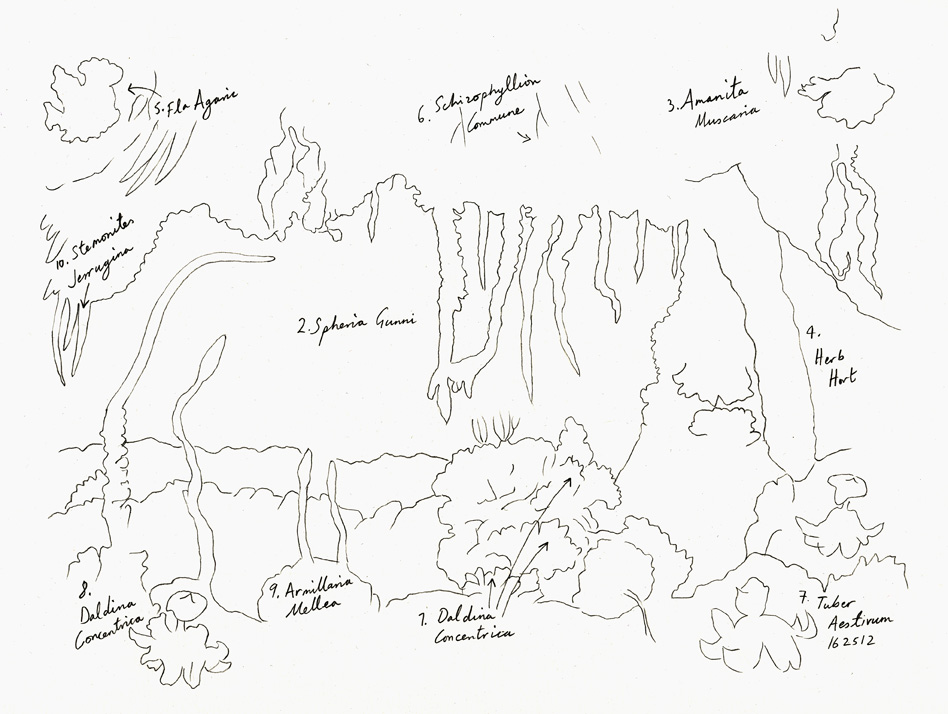

I regularly draw from natural science collections at these institutions. Taking them as my starting point, I began an inquiry by contacting individual archaeologists, astronomers, botanists, geologists, and mycologists. Through these dialogues, I gained opportunities to visit their workplaces, interact with their collections, and ask specific questions about drawing within their respective fields.

I was excited to discover that each department still maintains some element of drawing within its curriculum. Even when not formally part of the written course, passionate individuals within these departments still believe in the importance of analogue drawing compared to other observational methods.

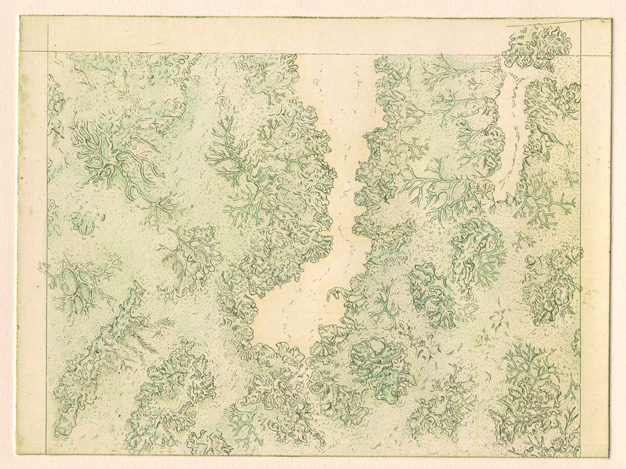

For this project, I selected historical drawings from each subject area that functioned as both works of art and science as inspiration. I aimed to substitute forms in these historical images with specimens from the collections bearing anatomical resemblances—for example, replacing R. Hooper’s anatomical drawing of a brain hematoma with the mineral hematite.

The works presented here are all drawn from direct observation of collections at Kew Gardens, UCL, the Natural History Museum, and UCL’s Observatory at Mill Hill. Each image reflects on the history of drawing within a particular branch of natural science, taking compositional inspiration from historical scientific illustrations.